Blog

Will you notice Google updates on the XmR charts?

Website traffic data typically looks like this:

Ups and downs, peaks and troughs.

If we do our job properly, we expect traffic to enhance over time, but it’s difficult to say whether there’s a peak or a dip to look out for in any given month.

Did we do something huge and start a recent phase of growth? Did we benefit from a recent Google update? Or is this just normal variation, part of the natural ebb and flow of people finding our site?

Or let’s say you made a change to your content process—pruning and redirecting a lot of aged content—and then your traffic dropped the next month. Did that drop caused by change or was it just a coincidence?

I experimented with a uncomplicated statistical tool to aid answer the following questions: XmR Chartsalso known as process control charts.

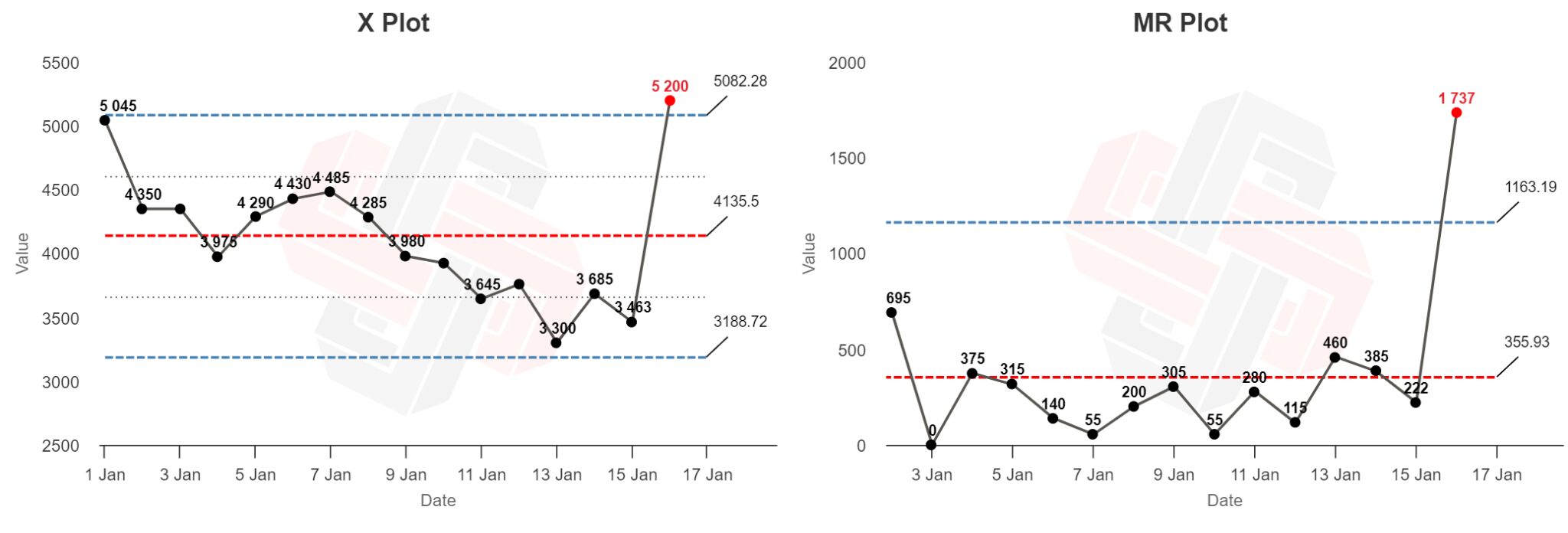

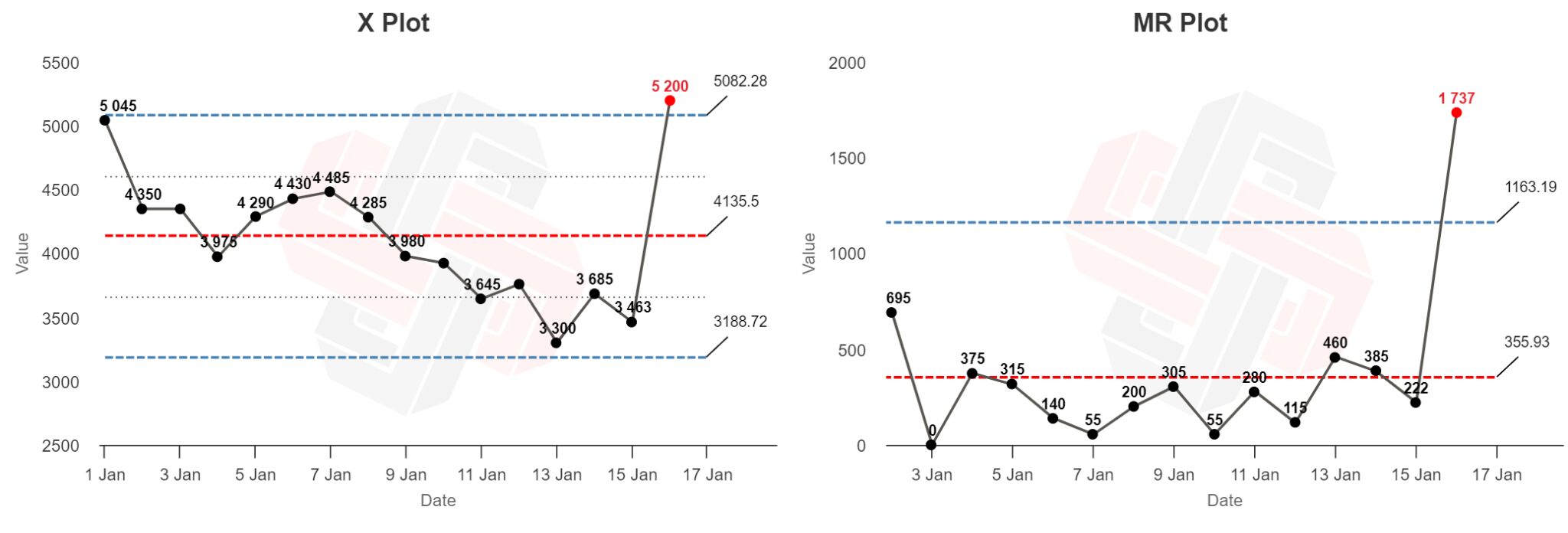

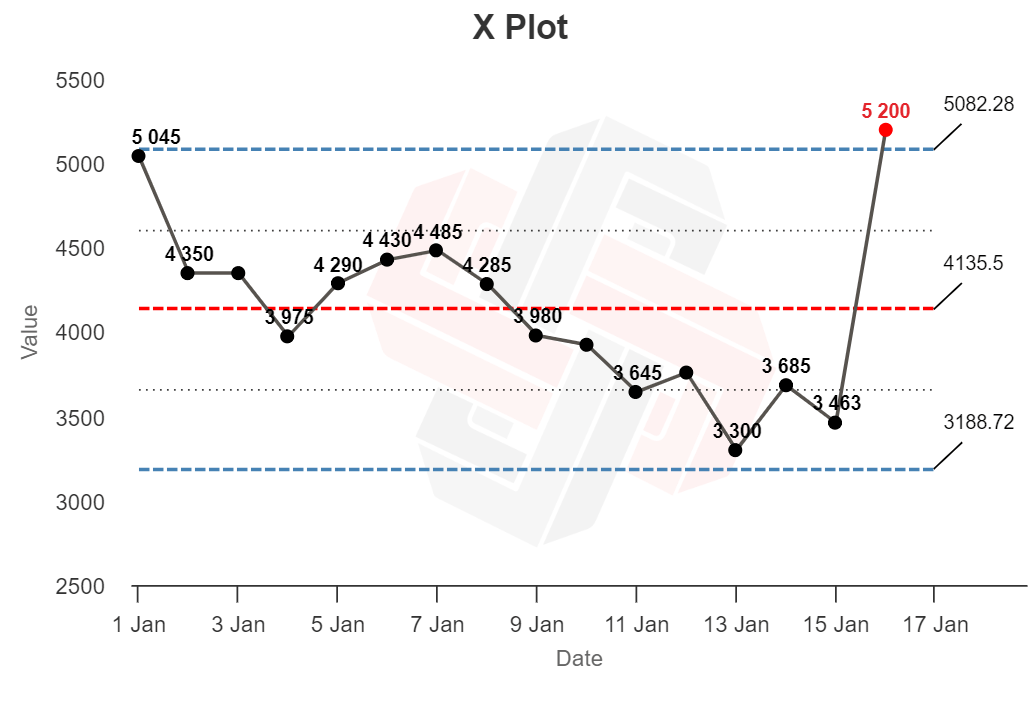

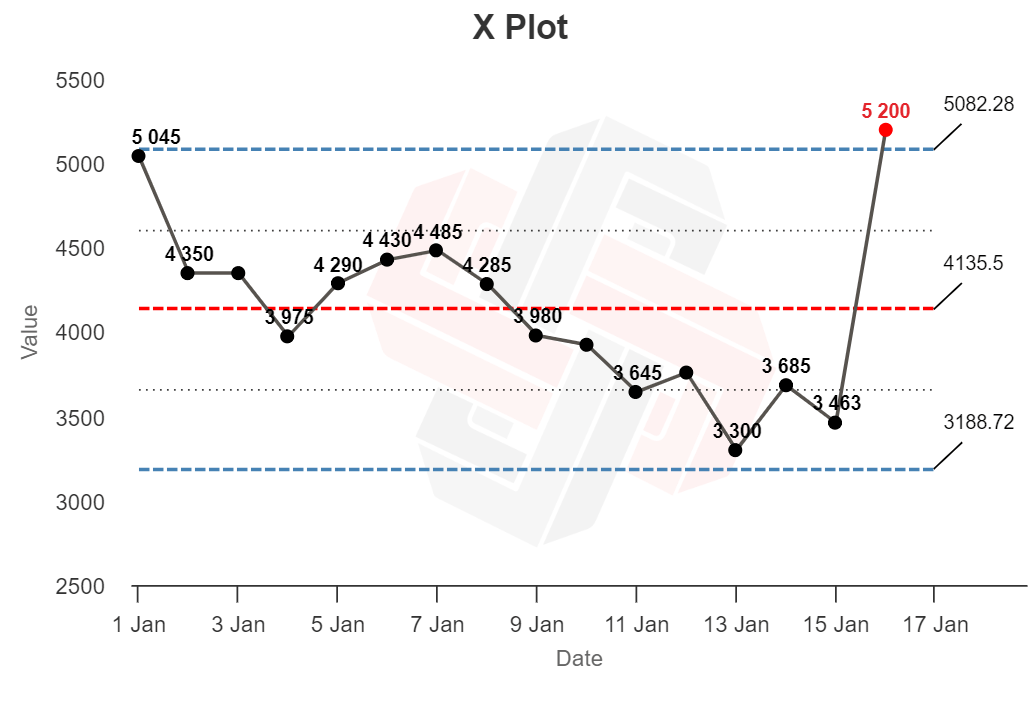

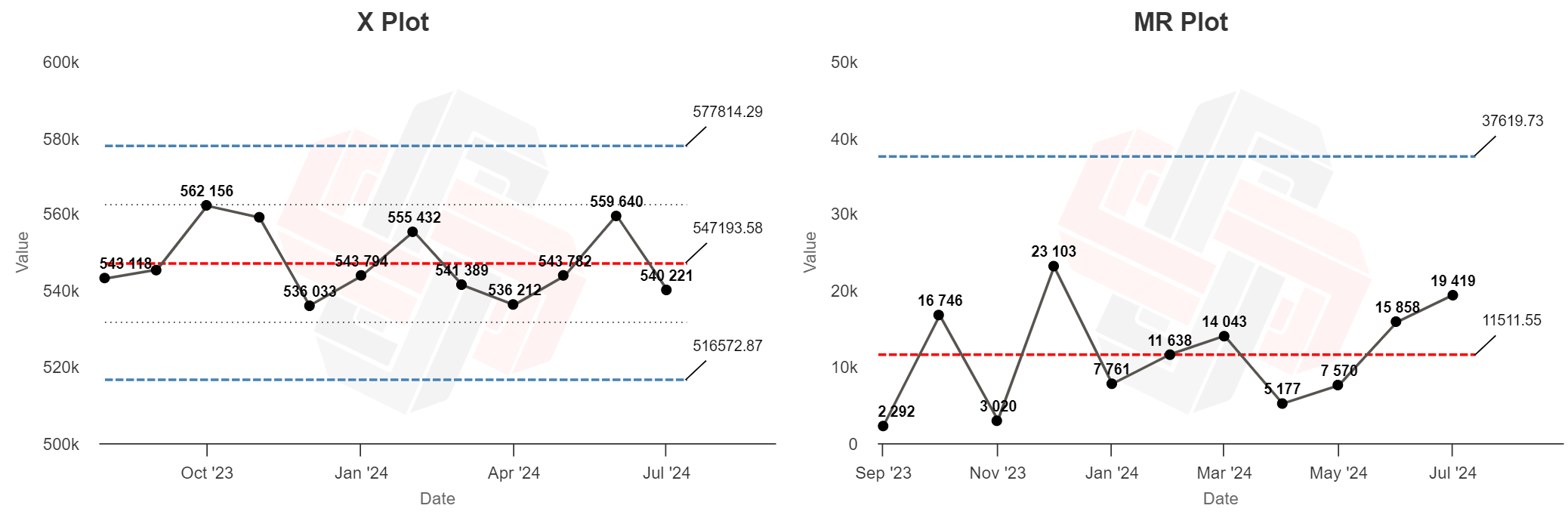

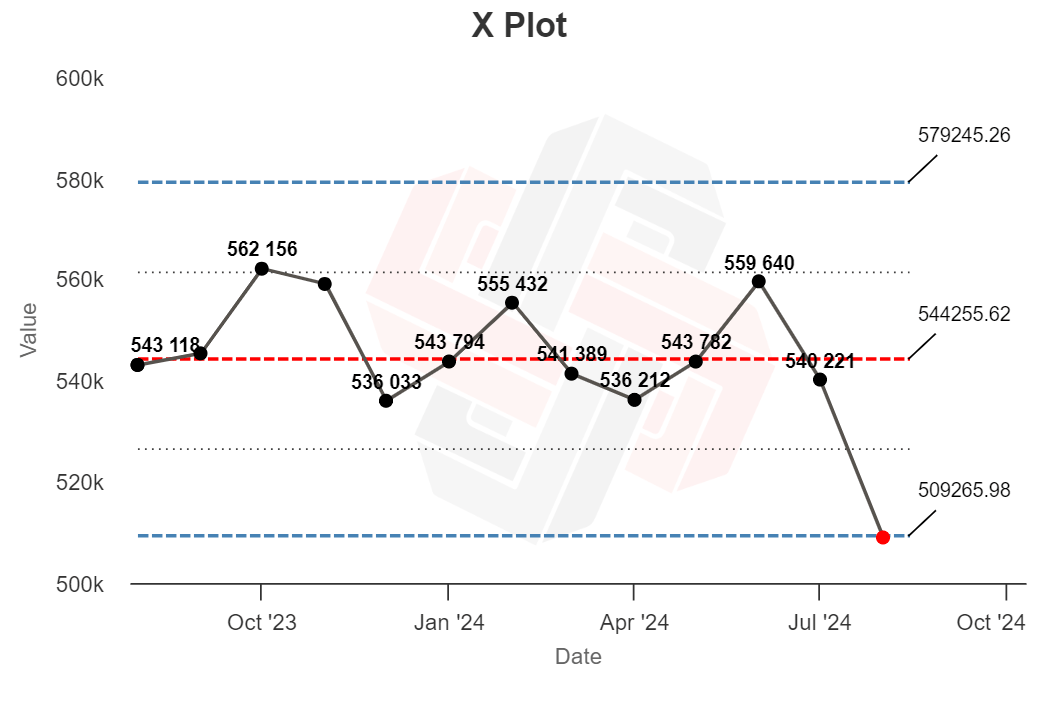

Here is the XmR chart:

XmR charts are designed to tell you whether any individual data point in a time series is likely to be due to normal fluctuations (“routine fluctuations”) or is a sign that something has happened and should be investigated (“exceptional fluctuations”).

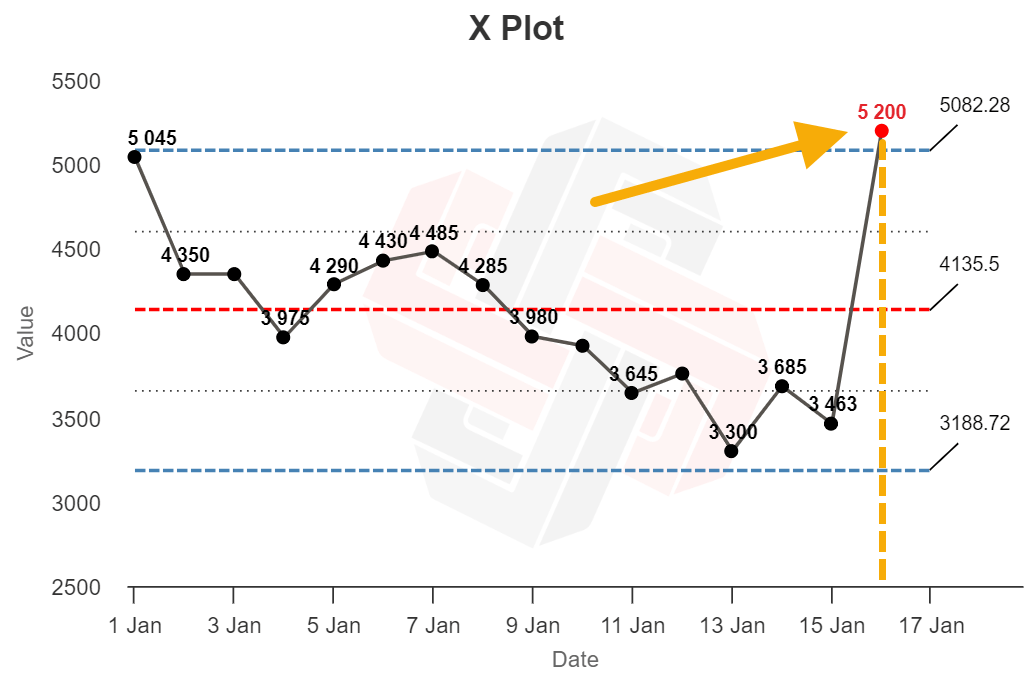

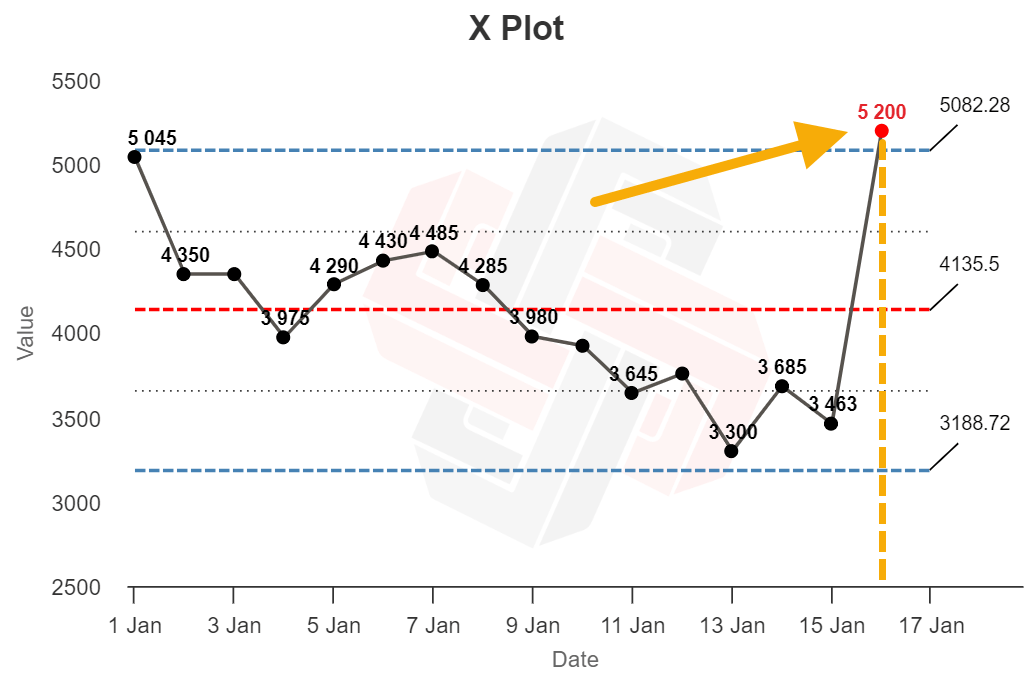

XmR charts consist of an X chart (named after value x“thing” we care about — like manufactured gadgets or a completed sale)…

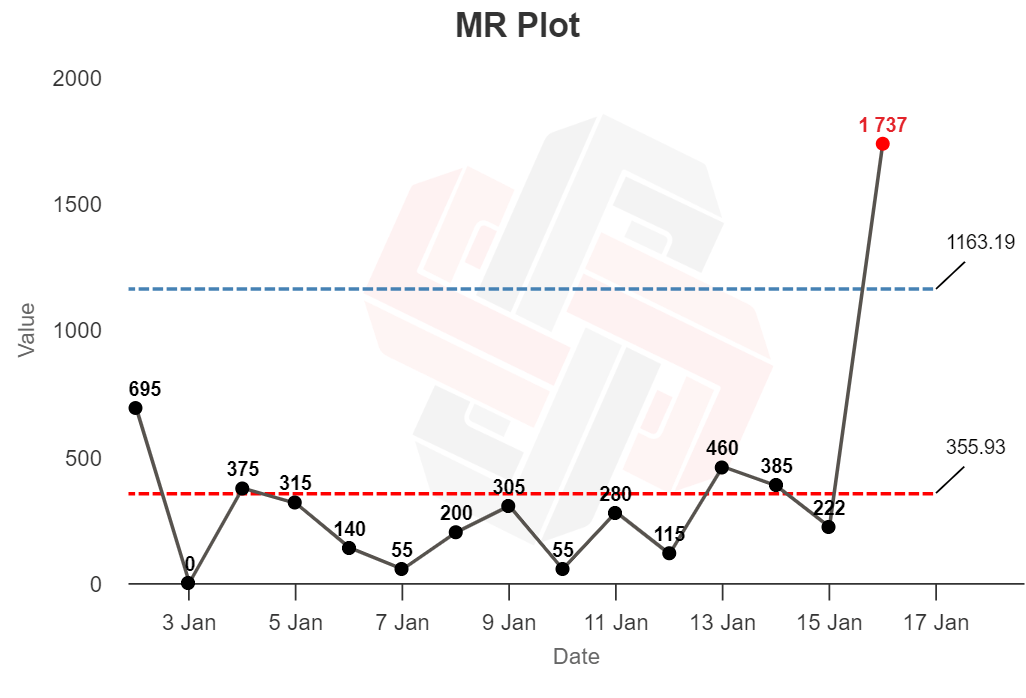

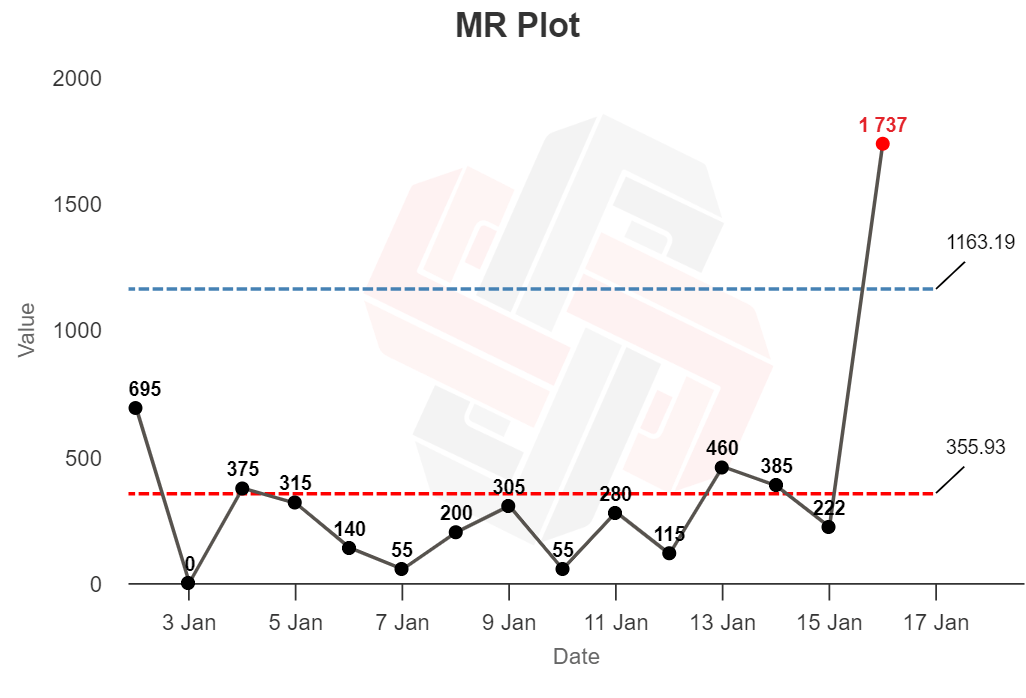

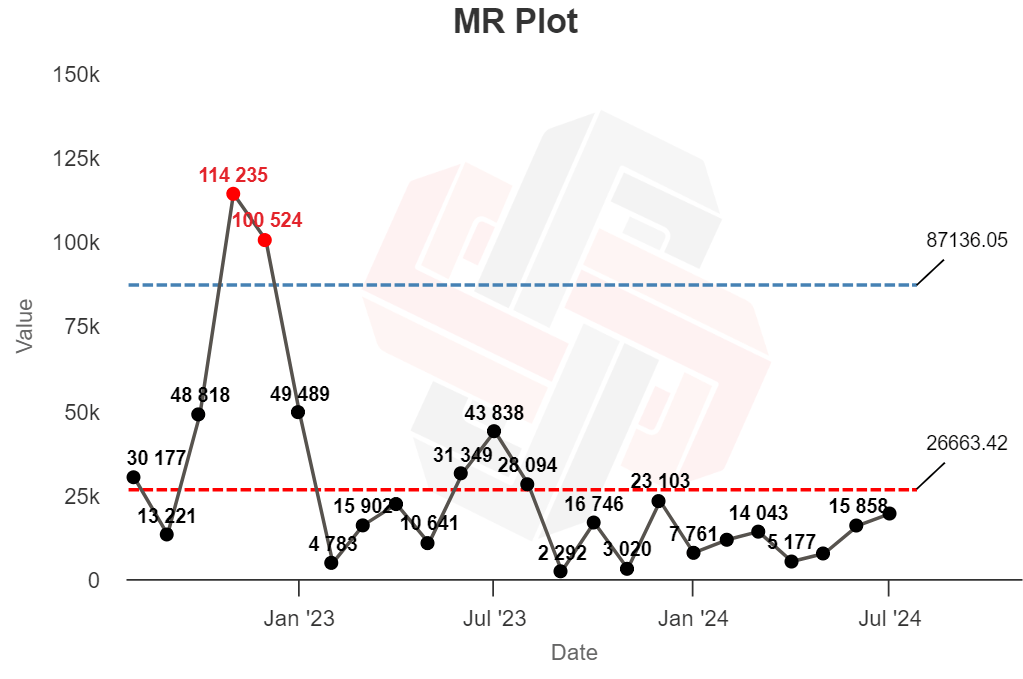

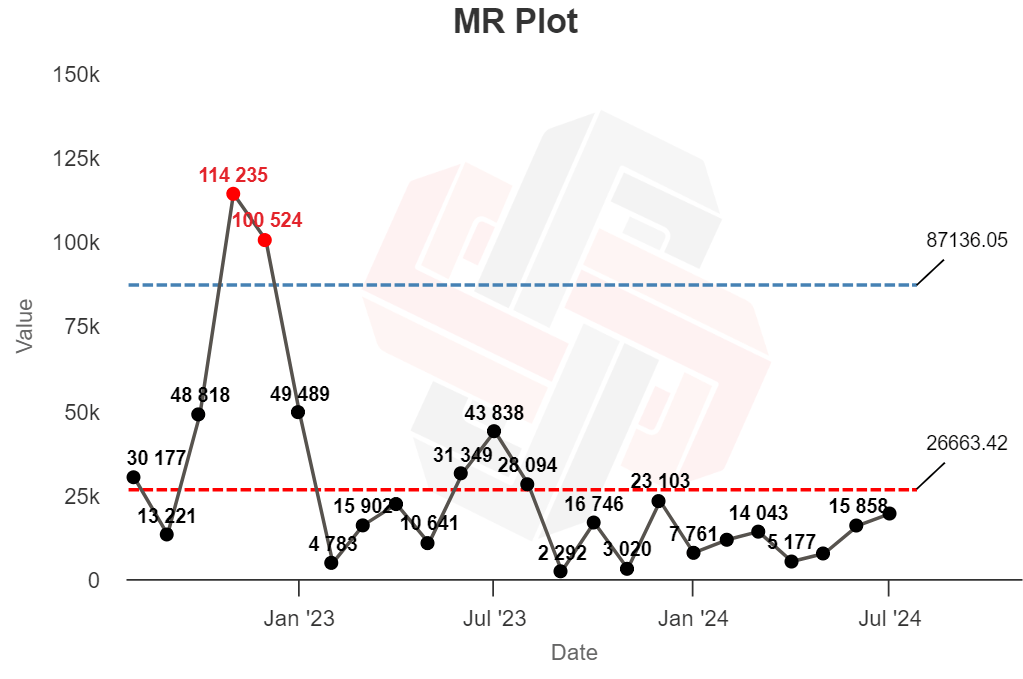

…and the MR chart (named after range of motionbasically the “gap” between each data point):

In its simplest application, if you plot your data on a chart and it gyrates up and down around the centerline without crossing the high and low boundaries—no problem! Those ups and downs probably represent normal volatility.

But all points that appear outside the upper or lower limits (shown in red) should be treated as anomalies that require investigation.

In the X chart above, the time series appears to show routine fluctuations until January 16, when the first red dot appears outside the bounds.

The XmR chart suggests that something happened on the 16th to screw up our production process (for better or worse). Our job is to investigate why.

Digression.

The line in the middle is the mean value of the data set; the upper and lower limits represent 3 standard deviations from the mean (known as three sigmas). Any point that falls outside these upper and lower bounds is most likely an anomaly and not part of the original probability distribution.

There are other “signals” that the XmR chart can show (e.g. eight consecutive points on one side of the average line representing another type of exceptional volatility) — but I’ll leave you to explore those at your own pace.

When I started reading about XmR charts, one obvious operate case came to mind: identifying the impact of Google algorithm updates.

If your traffic drops to zero, it’s uncomplicated to say, “We’ve been manually penalized.” But for smaller changes, like a few months of traffic drops, it’s harder to pinpoint the cause. Were we caught off guard by a Google update? Is this seasonal? Or is it just a coincidence and traffic will likely return to normal in the future?

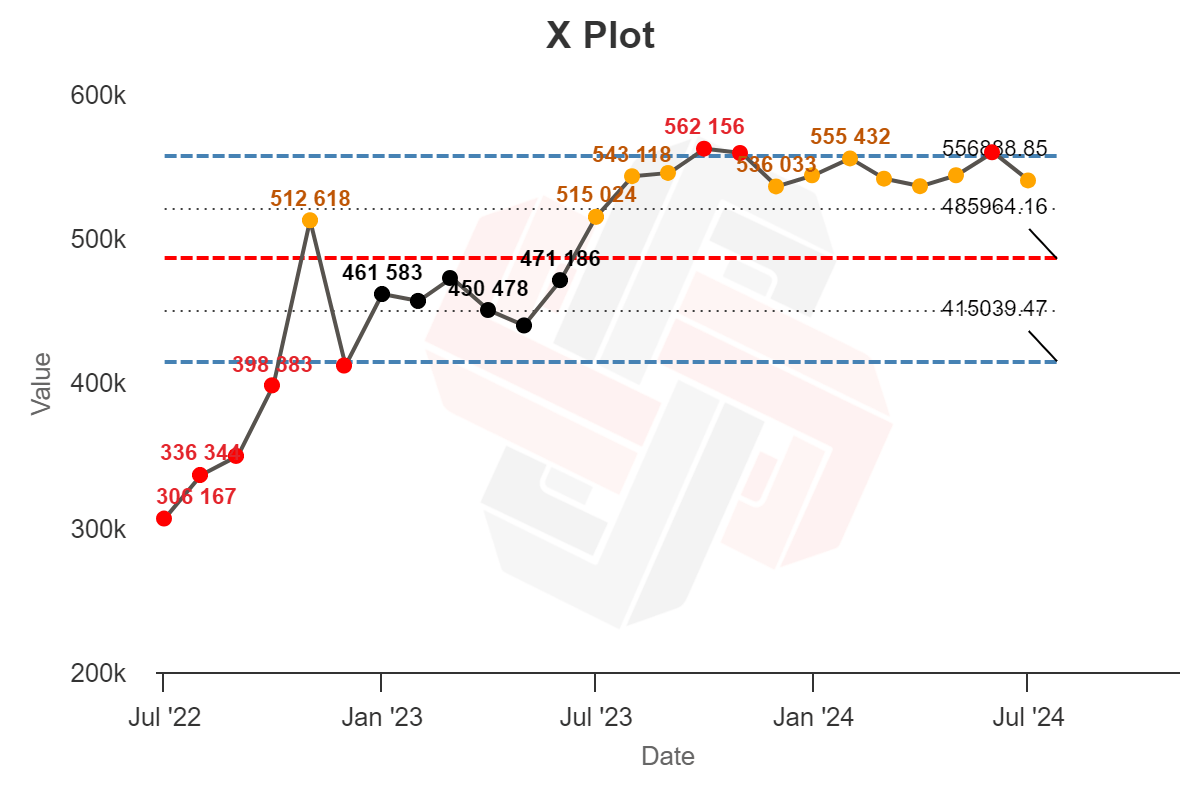

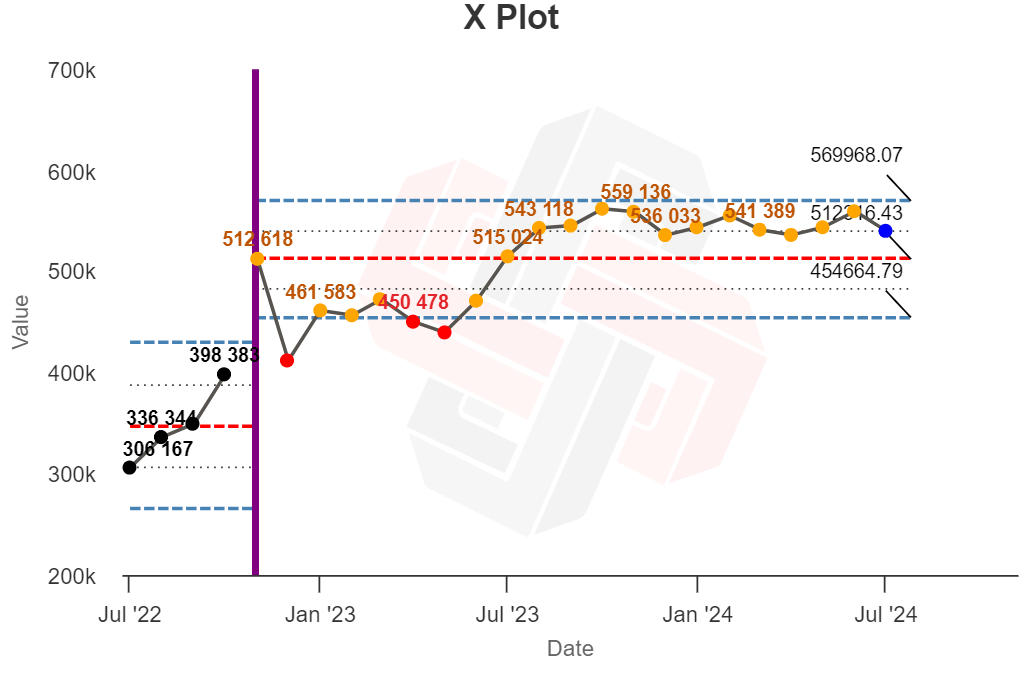

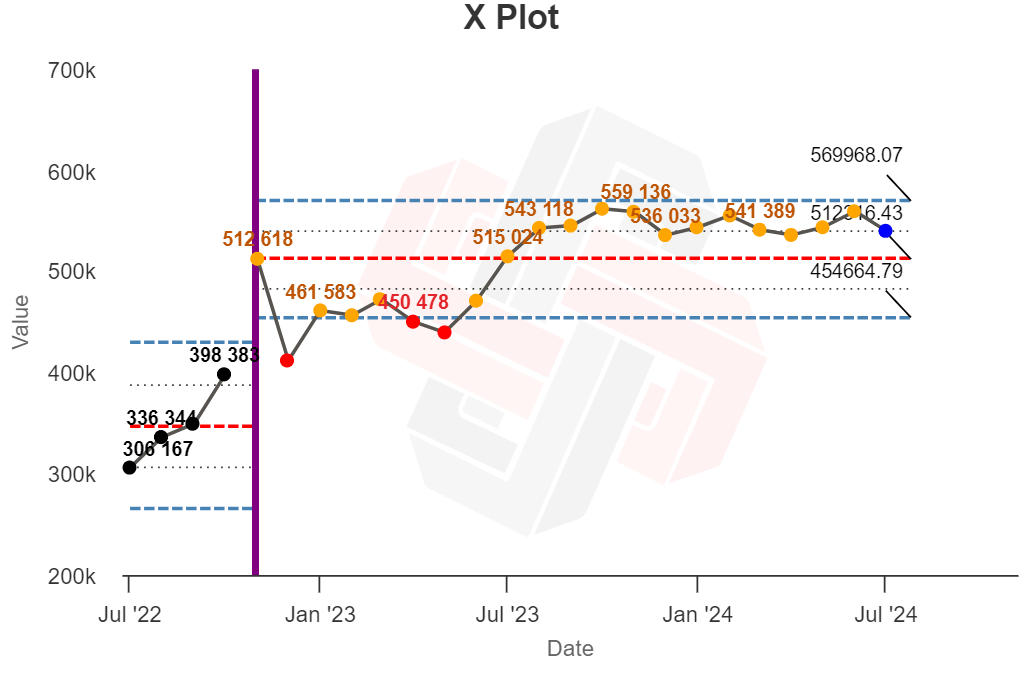

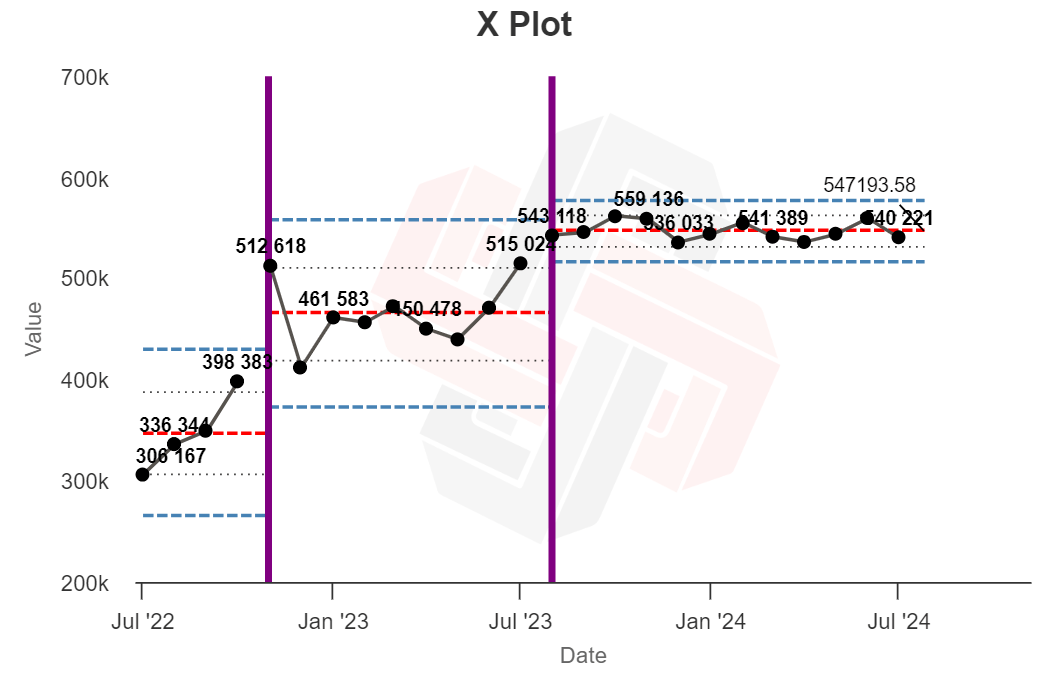

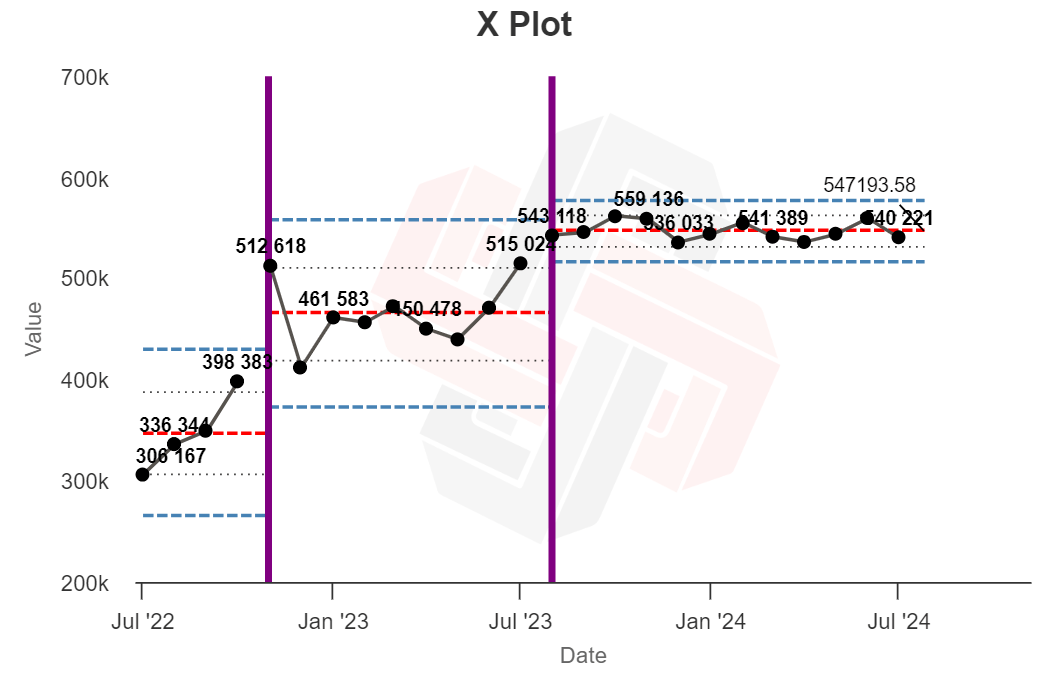

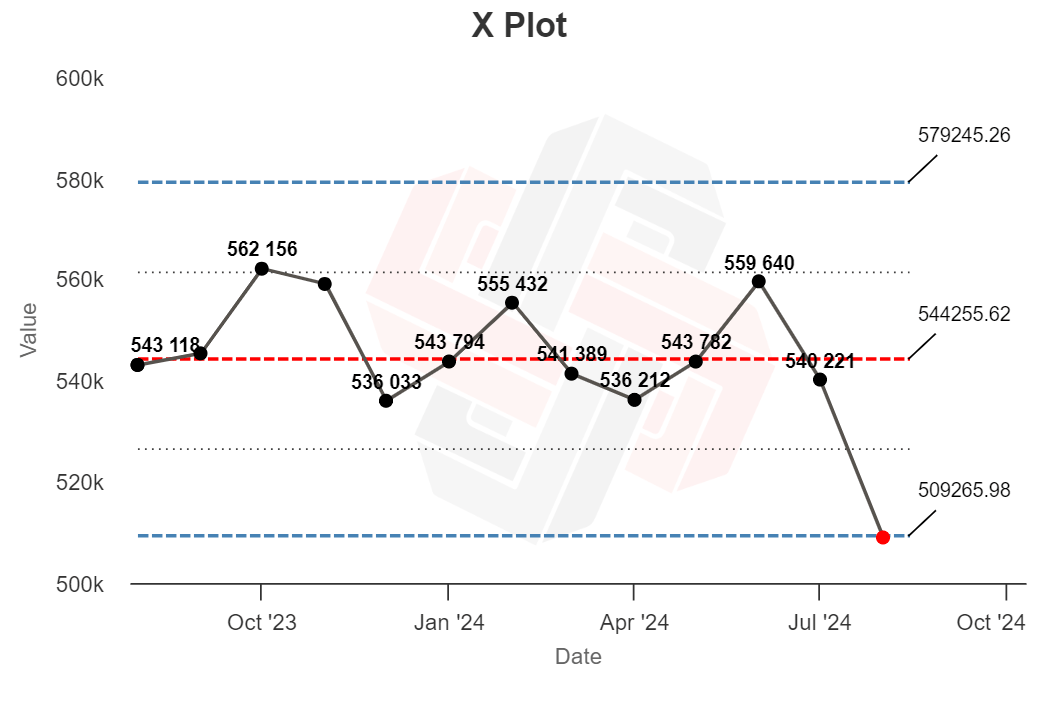

Here is two years of monthly organic traffic data for the Ahrefs blog, taken from Site Explorer and plotted in an XmR chart:

Well… that’s not particularly useful.

Many data points fall outside the expected range (red), and very few fall closer to the center line than the quartile boundaries (orange).

The XmR chart is supposed to show extreme variability in a consistent process—but in this image, almost every data point suggests extreme variability. What’s going on?

Process charts are designed for uncomplicated manufacturing processes and work very well when the expected process outcome is constant.

If your goal is to produce 10,000 widgets per week, the XmR chart will aid you determine whether a month of selling 5,600 widgets was a normal “accident” in routine business, or if there was a real problem that needs to be investigated.

Website traffic is more complicated. There are a lot of variables that affect traffic:

- fluctuations in search volume for each topic,

- positions in the individual ranking,

- recent competitive articles,

- search functions,

- seasonality,

- frequency of publication,

- Google algorithm updates…

This means that running an XmR analysis on a long series of traffic data probably won’t be very helpful. Your “blogging process” probably won’t remain stable for long.

In my case, this particular two-year dataset likely does not come from a single, stable process—there may be multiple probability distributions hidden within it.

But we can make this analysis more useful.

Best practice with XmR charts is to limit your analysis to a period where you know the process was relatively unchanging, and recalculate it if you suspect something has changed.

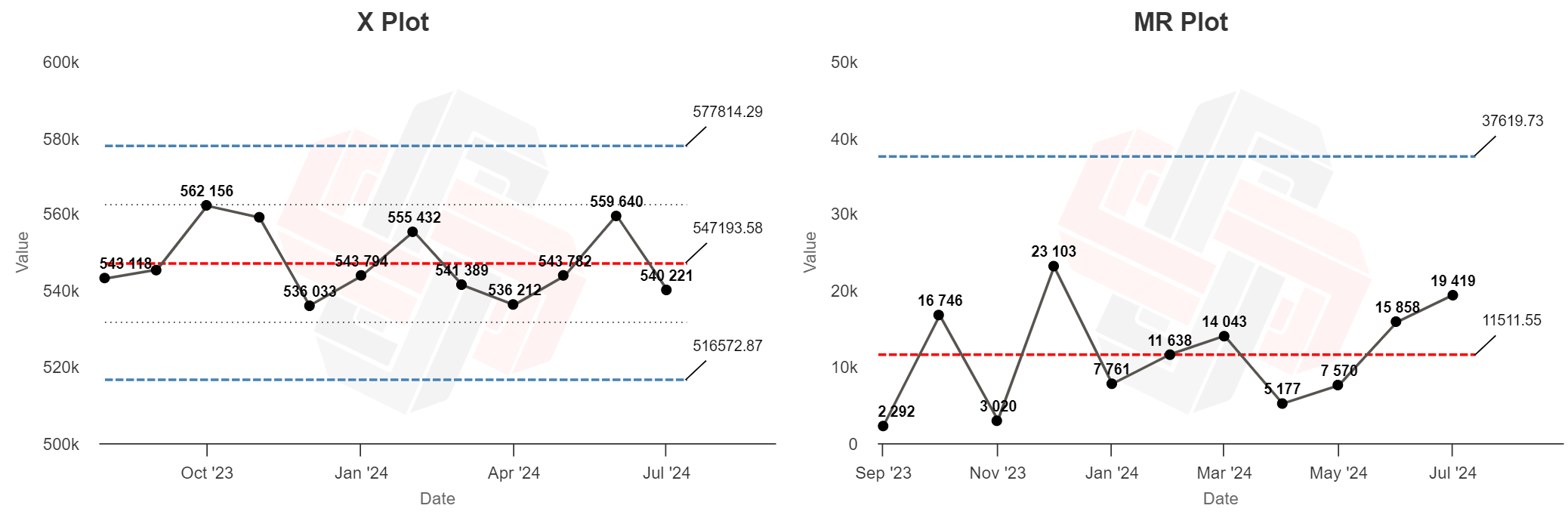

Looking at the Moving Range chart for this data below, gigantic amounts of movement deviation occurred in November and December. We should investigate possible causes.

I know our publishing frequency has been pretty unchanging (we definitely haven’t doubled our content production). Seasonality would have caused a drop in traffic, not a spike (we’re writing about SEO, not holiday gift guides).

But in early December, a huge Google update came out:

If we assume that something happened to our blogging process at this time — likely due to the change in traffic due to the Google update — we can add a divisor to our XmR chart.

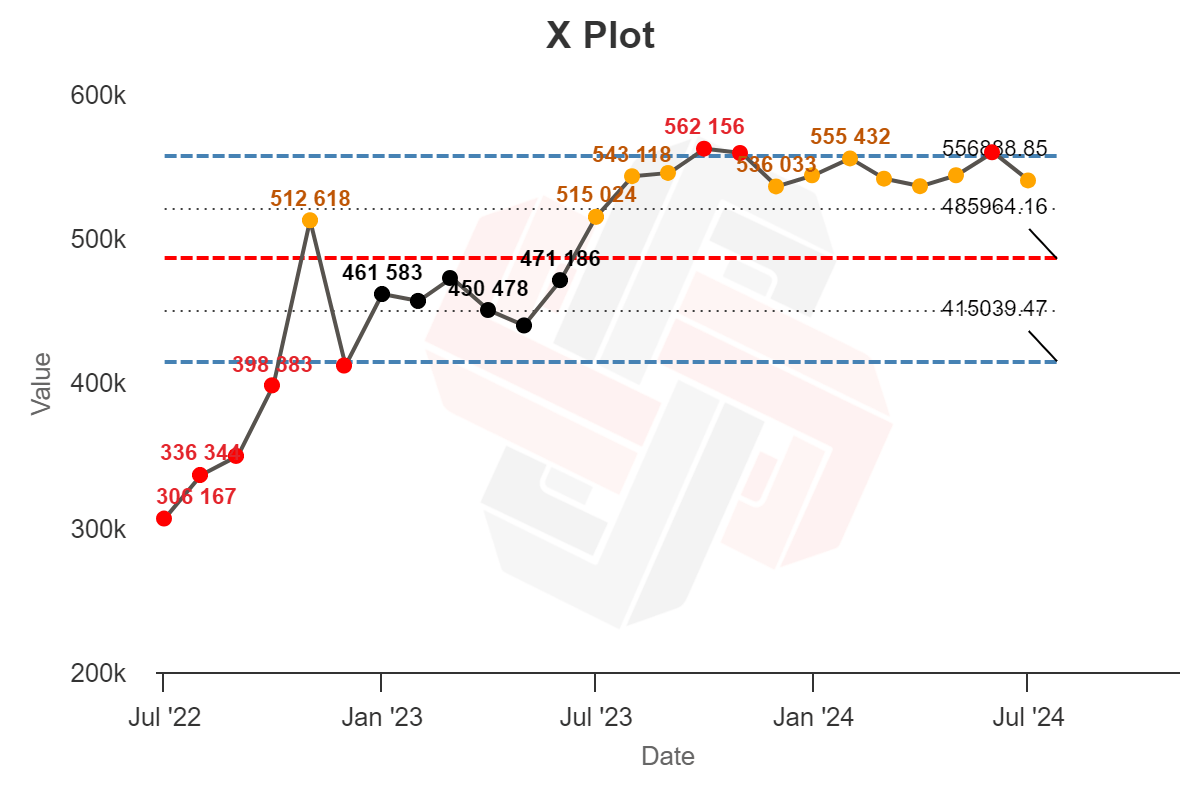

Instead of trying to analyze the traffic as a single process, we can treat it as two processes and calculate the XmR graphs separately:

Now the first process looks stable (all black dots). The second process also shows less extreme variability (red), but there is still too much moderate variability (orange) to look stable. There may be another process lurking there.

And according to rule of thumb for XmR chart analysis: “the XmR chart duration should be re-examined when the “long-term” data range remains above or below the mean line.” This trend starts in overdue summer (which is also around the same time Google announced the next major update):

At the beginning of this “long period” of data, we can add another divisor to create three separate XmR analyses:

In this way, all three analyses appear stable, with no extreme variance points. In other words, we seem to have done a good job of capturing three separate processes is happening in our traffic data.

This analysis shows that there is a high probability that our traffic was affected by external factors during the period of two major Google updates.

Now… this is essentially a post-hoc exercise in data torture. We cannot infer any causal relationship from this analysis, and it is entirely possible that other arbitrary partitionings would have yielded similar results.

But that’s okay. These charts can’t give you definitive, concrete reasons Why Your traffic has changed, but they can tell you that where to lookand aid you determine whether troubleshooting traffic declines or increases is a good way to spend your time.

The ultimate measure of a model’s usefulness is its ability to aid provide things. Will XmR charts aid me run my Ahrefs blog better in the future?

I think so.

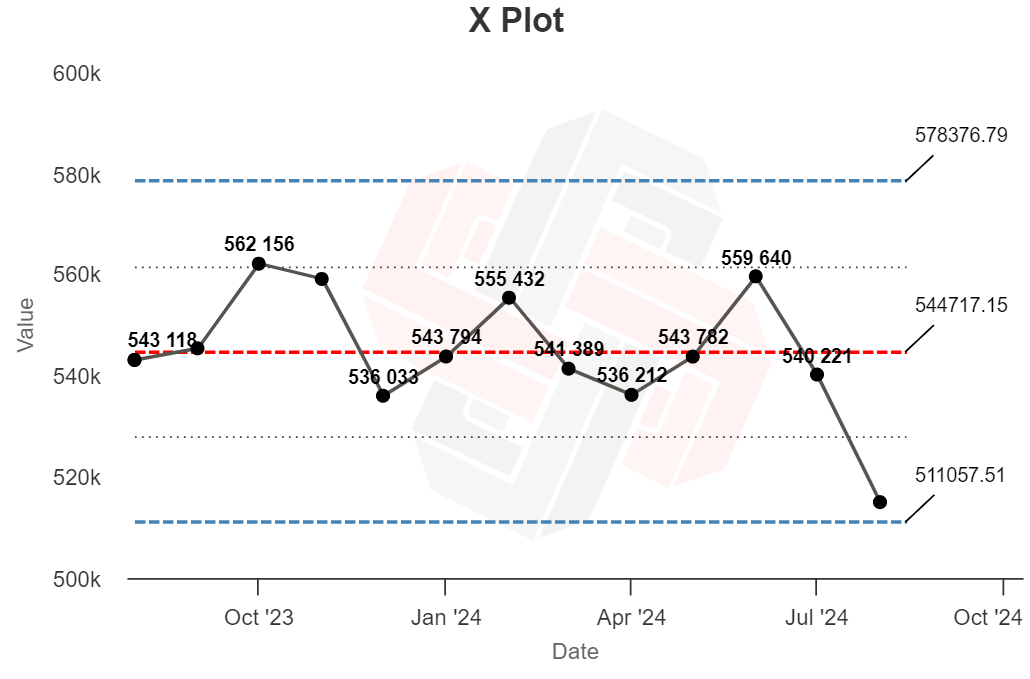

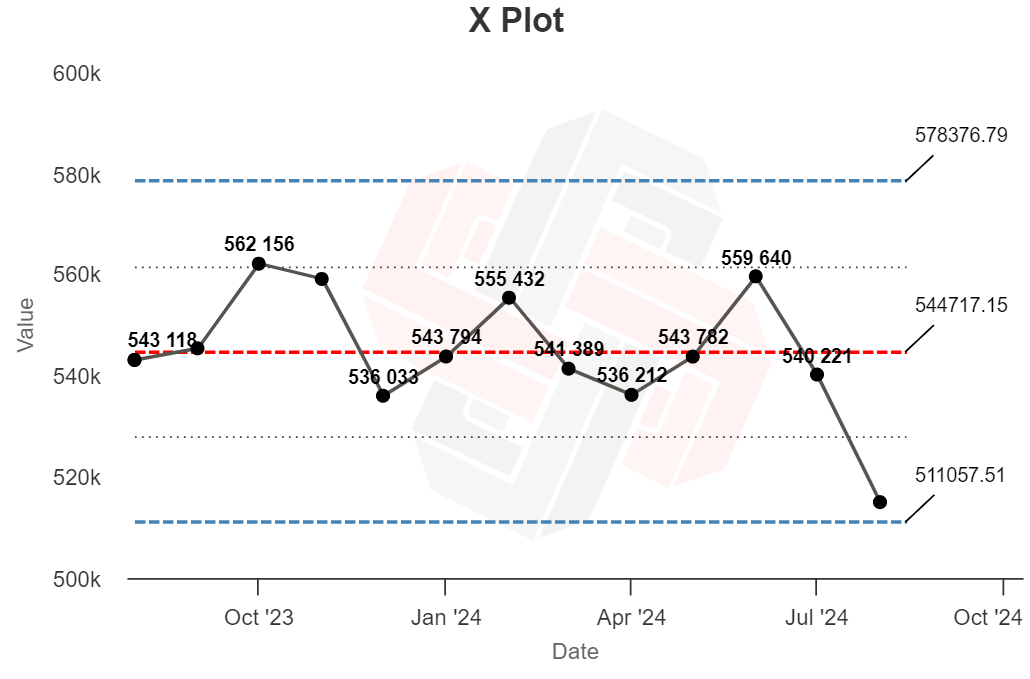

Assuming my “blogging process” remains relatively stable — I post at the same frequency, cover the same topics, compete with the same competitors — I now have a set of “stable” metrics I can operate to provide additional context for future traffic numbers:

In the coming months, I will be able to assess whether the drops and increases in traffic are most likely the result of normal variations or if something has happened that requires my attention, such as a Google update.

If, for example, my move next month is like this…

…I know that given this distribution, the drop in traffic may be a normal, unexciting deviation.

But if that happens…

…there’s probably something else going on.

With extreme traffic changes, you can usually “watch” the traffic charts and guess what happened. But XmR charts are useful for more subtle changes, and there’s a chance I’ll be able to identify and take action based on a single month’s worth of data. That’s pretty chilly.

Final thoughts

Troubleshooting changes in web traffic is a huge challenge for SEOs and content marketers (we’re working on a few ways to aid you spot the signal amidst the noise of your web traffic data).

In the meantime, I’ve found the XmR charts to be an engaging tool in my toolbox, useful for contextualizing monthly data in reports and justifying when I should (or shouldn’t) devote energy to troubleshooting a bad month.

(XmR charts can at least give you the confidence to say “get off my back” when your VP sends you a parched email at 3 a.m. complaining about an 8 percent drop in traffic last month.)

Digression.

Thanks Benjamin ElijahVP of Marketing at Podia, for introducing me to XmR Charts.