Blog

This long weekend, delve into the intricate roots of gardening – listen

The May long weekend is the unofficial start of summer. And for those of you with gardens or access to public spaces, it’s a weekend to dust off your gardening tools and visit a garden center to kick off the upcoming growing season.

As the gardening season begins, it’s worth asking yourself a few questions about its origins.

Whether you plan to grow marigolds, start a vegetable garden, or create a place where pollinators can grow, all gardens have sophisticated roots.

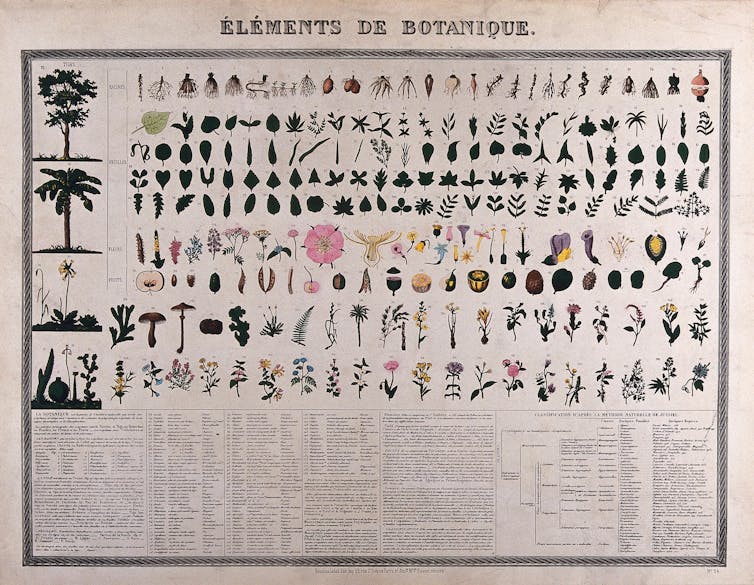

In fact, the practice of gardening is deeply connected with colonialism – With the formation of botany as a sciencedown dissemination of seeds, species and knowledge.

In this episode of Don’t Call Me Resilientwe explore the sophisticated roots of the garden, including who can grow the garden. We also discuss practical tips for what to plant with Indigenous knowledge in mind. We talk with researcher Jacqueline L. Scott, as well as community activist Carolynne Crawley, who leads workshops that integrate Indigenous teachings into practice.

Pietro Antonio Michiel, Venice ca. 1550–1576, Biblioteca Nationale Marciana.

Desirable tulips

Some of the most recognizable plants today include: Tulipsare the result of early colonial conquests. Originally growing wild in the valleys where present-day China and Tibet meet Afghanistan and Russia, tulips were cultivated in Istanbul as early as 1055.

Later, when the Dutch crossed them and turned them into a commodity, they became an extremely desirable status symbol because of their lovely but fleeting flowers.

The exploratory botanical expeditions of European colonial powers were an integral part of the expansion of empire. These journeys fueled a immense business of collecting global plant samples, and also led to the emergence of botany as a scientific discipline.

CC BY-NC

Botanical gardens served as laboratories

Botanical gardens played a key role, serving as laboratories where plant specimens were organised, ordered and named. “Scientific objectivity” presented a Eurocentric point of view, disrupting and displacing indigenous knowledge and ecological practices.

Jerome H. Farbar: “Houston: Where Seventeen Railroads Meet the Sea.” Page 31/40, “The Cotton Pickers”, Legal disclaimers

The movement and transfer of plants around the world went hand in hand with the transportation of people to provide the labor, through slavery and indentured labor.

The plantation system has led to the destruction of local ecosystems and the replacement of time-honored agricultural methods with the cultivation of commercial crops such as sugarcane, tea AND cotton. These were products intended for European curiosity, markets and profit, not for the local population.

Plant and racial hierarchies

This colonial system organizing agriculture laid the foundation for categorizing people Similarly, a social hierarchy was established that dehumanized non-Europeans, which helped justify slavery and genocide of indigenous peoples, and ultimately led to the creation of racial categories.

This history has shaped our present relationship with the land and our gardens. It also informs beliefs about ownership and access to land; who has the right to operate the land and who gets to work it. Who has the literal and figurative space and freedom to garden?

Changing attitudes

But the soil is changing. There is a growing shift away from colonial lawn status symbol AND well-kept gardensin favor of the pollinator friendly native plants.

The belief that centuries-old indigenous knowledge based on the land and practices – such as controlled burns — can assist manage forest fires and create a more resilient landscape.

Given the growing concerns about the climate crisis, one possible avenue for creating more sustainable cities could be our gardens.

Could we have an impact simply by thinking a little differently about the seeds we sow and the “weeds” we pull out?

Jeffrey Hamilton/Unsplash

Listen and follow

You can listen or follow Don’t call me resistant ON Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify Or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts.

We’d love to hear from you, including any ideas for future episodes. Join The Conversation on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram AND TIK Tok and operate #DontCallMeResilient.

Resources

Tiffany Traverse on Seeds and Their Infinite Power to Give, Heal, and Grow – National Observer of Canada

Colonialism of Planting: Legacies of Racism and Slavery in the Practice of Botany – Architectural review

The Long Shadow of Colonial Science – Noema Magazine

Is it time to decolonize your lawn? – Globe and post office

Turtle protectors in High Park in Toronto

Spring joy with Ateqah Khaki – Gardening Out Noisy

From the archives – on The Conversation

Read more: How the Botanical Gardens’ Colonial Past Can Be Put to Good Employ

Read more: Kew’s science director: time to decolonise botanical collections

Read more: Native seed shortages leisurely land recovery across the U.S., key to combating climate change and species extinctions

Markus Spiske PG/Unsplash