Blog

On the Art of Physical Exercise, a 16th-century account of age-old sports and exercises

According to World Atlas of ObesityBy 2025, 42% of the world’s population will be overweight or obese. Lack physical activity is one of the main causes. Experts respect This was considered a solemn health problem. Even in Greco-Roman times, doctors believed that being overweight was bad for your health.

Doctor Rufus of Ephesus (dynamic in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD) wrote a book titled About weight loss for obese people. Fat people, he suggested:

they cannot bear excessive exertion, hunger and indigestion, they feel discomfort because of this and become seriously ill.

Many Greek and Roman physicians recommended that people lose weight by running and eating only one meal a day. But if you want to know what most people in Greco-Roman times thought about the relationship between exercise and health, the best source of information is Girolamo Mercuriale‘S On the art of physical exercise.

Published with acclaim in 1569 and illustrated with drawings of the artist’s exercises Pirro LigorioMercuriale’s book was reprinted several times during his lifetime. In 2008, a luxurious, 1,000-page edition was published. edition with an English translation of the original Latin text, was published on the occasion of the Olympic Games in Beijing.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Author

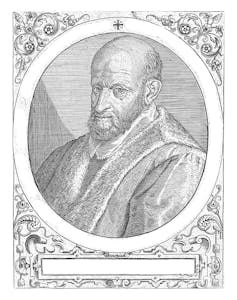

Mercuriale was born in 1530 in Forlì, Italy, and studied medicine and philosophy. In the early 1560s, he became a personal physician Cardinal Farnesegrandson of Pope Paul III. During this period Mercuriale, who was very aware of the different attitudes towards health and physical fitness in age-old times and in his own time, wrote On the Art of Physical Exercise.

From his perspective, Greco-Roman physicians placed great value on exercise as part of a fit life. In contrast, physicians of his day were little concerned about it.

Wikimedia Commons

In his opinion, many people in his time lived idle lives and neglected their physical health, which could be improved by exercising more.

In age-old times, people exercised in public gyms (the equivalent of newfangled gyms) or, if they were wealthy, sometimes in private gyms in their homes. People also exercised in nature.

Interestingly, like many age-old physicians, Mercuriale believed that being a professional athlete was detrimental to one’s health because it required an excessive, unbalanced lifestyle. Archaic athletes had to follow a strict diet and often tore muscles or injured joints due to overtraining.

Walking

One of the exercises favored by Mercuriale and his age-old sources was walking. He writes:

The ancients valued walking so highly that both in private gymnasiums and in gymnasiums and elsewhere they devoted no greater attention or zeal than to building places suitable for walking.

In Greco-Roman times, people exercised by walking along enormous public porticoes, on open walking trails, or in underground passages (designed for exercise in inclement weather, such as during heat or storms).

Some age-old physicians believed that walking on a route that went up and down hills was better for health than a flat route because it involved a variety of body movements. Others debated whether it was better to walk on paved roads, dirt paths, or sand.

Even the Romans Emperor Augustuswho lived from 63 BC to 14 AD, exercised by walking on sand. As Mercuriale writes:

When walks are made on sand, and especially on deep sand, they are very effectual in hardening and strengthening every part of the body. Augustus, therefore, as he did not enjoy good health in his hip, left thigh, and leg (he often limped on that side), strengthened them by walks of this kind.

Snapshot

Ball games

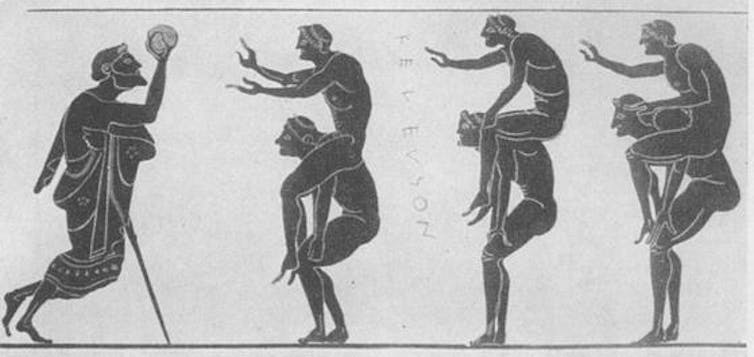

Another type of exercise preferred by the ancients was ball games.

There were many types of ball games in age-old times, including one called “Episcyrus,” a type of handball. Mercuriale describes the game as follows, based on the account of the 2nd-century AD Roman author Julius Pollux:

An equal number of players are assigned to two teams, and a center line, called a “scyrus,” is drawn on which the ball is placed. They then compete to score between two lines drawn behind each competing team, called goals. Of course, the first to do so wins. While the players were busy catching the ball, throwing it back, dodging it, chasing it, loudly cheering each other on, and encouraging each other, both players and spectators were probably delighted.

Wikimedia Commons

Some age-old physicians believed that ball games like this were the best kind of exercise because they were good for both the body (through physical movement) and the soul (through teamwork and camaraderie).

Greek doctor Antylus (2nd century CE) said that ball games harden the body, giving great strength to the arms, back, sides, chest, and legs. Antyllus regularly prescribed ball games to his patients.

Other exercises

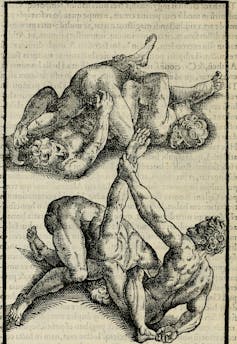

The most popular gym activities included running, wrestling, weightlifting, rope climbing, and boxing (with a partner or with a punching bag filled with sand or grain suspended from the ceiling).

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The ancients also practiced martial arts (combat sports), which involved donning armor and performing mock fights or wrestling.

Such sports, Mercuriale wrote, were played “with imitation weapons that do not strike difficult or cut a man.” Or, alternatively, they were played “against a column or a post, or even against a shadow.”

Swimming was extremely popular – in the sea and in the pool – and was held in such high regard, writes Mercuriale, “that children were taught the art of swimming as well as the basics of reading and writing.”

Doctor Antyllus said that people swimming for sports purposes should “first take advantage of a moderate massage and hot up by rubbing the body, and then immediately jump into the water.”

Snapshot

Greco-Roman physicians prescribed physical exercises of all kinds to their patients. An example of this is the case of an athlete Laomedon of Orchomenuswho lived in the 2nd century AD or earlier.

Laomedon suffered from a disease of the spleen (the age-old sources do not explain what his problem was) and his doctors recommended that he take up long-distance running. After several years of running in this way, he recovered. He also became one of the best long-distance runners of his time, competing in the Olympic Games.

A book for all times?

The advice in the book is addressed to everyone: men and women, juvenile and ancient, fit and ailing.

In the dedication at the beginning of the work, Mercuriale expresses the hope that his patron, Cardinal Farnese, will learn how to live healthier and take better care of his body by reading this work:

It remains for you, following the example of the ancients, to train your body to such an extent that you will not only attain the long life which Heaven promises you and which your nature suggests, but also, if possible, prolong it still further.

It is not known whether Mercuriale practiced what he preached and followed his own advice, or whether Farnese followed his recommendations.

Snapshot

Farnese died of apoplexy in 1589, 20 years after writing the above words.

Mercuriale married in 1571 and had five children with his wife Francesca. He died in 1606 in his hometown of Forlì from problems caused by kidney stones.

He wrote several other major works on medicine and the history of medicine, but none of them achieved the fame or influence of this work.